The Play Ethic

What would it mean to have a play ethic? It’s not the opposite of a work ethic – you can have both at once. But you can’t be depressed and feel like playing, so researcher Stuart Brown says it’s the opposite of depression.

Just as children learn to interact and feel competent in the world through play, there is compelling evidence that adults benefit from using play to explore, experience new ideas and learn. Games and fun break down social barriers, give opportunities for people to connect and understand things in new ways, and try out new realities.

Experimentation and tiral and error is a form of play. The Burundi Red Cross for example developed a whole network of community volunteers by designing, testing, adjusting and replicating on a small scale, before effectively spreading the idea of community volunteering across the country.

Play is intrinsically tied to freedom and autonomy – it’s just not possible to be forced to play! Change processes in organisations can fail where people feel they have no stake in the process so engaging people in playful and relevant explorations can be highly motivating. In my experience both as facilitator and participant in workshops, games need to be relevant to the work being done – otherwise, even though it may help to relax the group, a game can be distracting and even irritating.

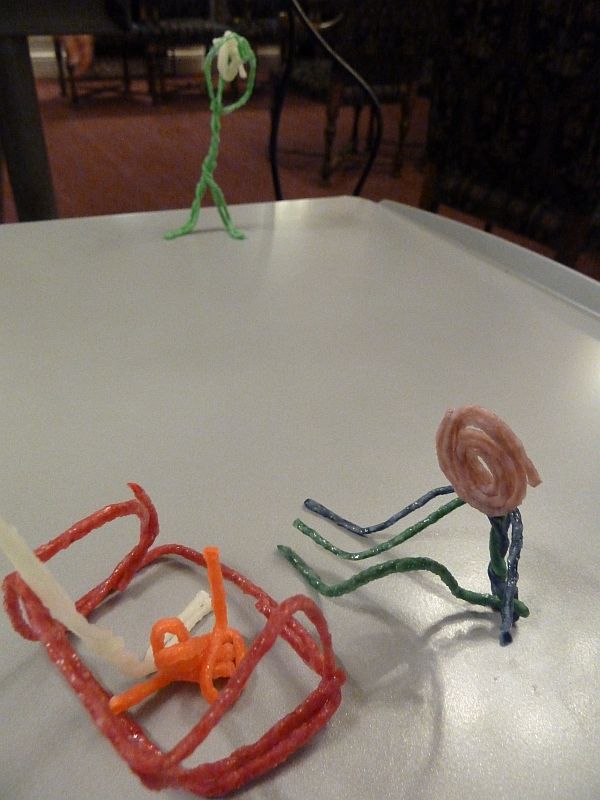

Modelling with pipe cleaners

But games are not the same as play. The challenge for us is to find the space for real play and creativity in our work. In Framework, we do this in our retreats, setting aside time for play with Lego or pipe cleaners (recent examples!) to explore how we are feeling about our work, or how we build relationships with clients. And in the moment, we let down our normal protections, show our vulnerabilities, enjoy ourselves, and feel more positive. For those who want to put their play ethic to the test, there’s a feast of funny games from Bernie DeKoven right here.